A glass fish for your TV set

Un peşte de sticlă deasupra televizorului

(A glass fish on top of the TV set)

<<Colorful mouth-blown glass fish were a must have in Romanian households up until the late 80’s. Manufacturing started long before this date and took place mostly in two factories founded in the 1800’s. Glass fish became articularly fashionable when the first TV sets started appearing in private homes in the 70’s. Early cathod ray TV’s were finished in wood and appeared as an empty shelf to their owners, specially when shut off. Decorating them with a glass fish (surmounting a white doily that prevented it from scratching the TV its self) was not seen as kitsch. On the contrary the fact that the screen was made of glass made this choice particularly coehrent and philological. Older specimens often present a mirrored surface and a sharply edged mouth. Color and size range are both very wide with length ranging from 20 to 60 cm.>>

True story of the ornamental glass fish

Crystal glass, Murano or Bohemia for connoisseurs, decorated the most highbrow homes of Romania, long before the advent of communism and of course long before televisions appeared.

Besides having an importan role from a cultural point of view, many Romanian cities such as Timişoara were extremely wealthy up until the first half of the XX century, as the façades of numerous buildings remind us. This is just to say that collecting glass has been “a thing” for centuries in this country.

The connection between the two items, the fish and the TV set, took place in the early 1970s when cathode ray televisions, far wider than today’s LEDs, appeared in private homes and became the expression of the most advanced technology of that time. The new device soon became a companion for every family who owned one. It was both a status symbol and a source of entertainment that left people in awe. It deserved to be valued and highlighted within the household.

Furthermore the top of the TVs was perceived as an empty shelf. The glass fish was originally meant to beautify the device and there was of course no intention of producing a Kitsch effect. Probably chosen by so many people for the fact that it is too a symbol of wealth and good taste, it has proportions that are well compatible with those of early TV sets.

Being the fish made of glass must have also been considered a particularly coherent choice given that TV screens are also made of glass. Soon millions of TVs across the country were decorated with glass fish. It was concsidered very precious object, very suitable to pair the TV which was possibly considered the most precious object of all in many households. Accidentally braking the fish was nothing short of a small catastrophe. All these fish that swarmed across Romania were locally manufactured, mostly in two different factories called Pădurea Neagră and Tomeşti.

One of the last practical uses of the glass of fish was in 1999: During the total eclipse of the sun, many Romanians who did not have special glasses watched the phenomenon through a glass fish. Shortly after, the advent of flat screen TVs marked the end of this strange trend.

All’Origine’s selection of glass fish

(photos by Simone Nocetti)

But why are e-bay sellers calling them Murano glass fish?

The easiest answer would be of course that more people search for “Murano glass” or even that fraudulent sellers would try to trick people as they might be more prone to spend on a blown glass item that is said to come from Murano rather than one from Romania. But is this really the case? Actually there is a lot of confusion and many people trading this kind of object are genuinely convinced they are from Murano, but as our research discovered, there have actually been, over the past one and a half century many contacts between Murano glass makers and Romanian factories, especially one called Tomeşti. We cannot prove or disprove this, but it is possible that of the many mid-century mouth blown fish still circulating a very small number might have actually been manufactured in Murano in ancient times. If you have any more information than what we were able to find, please do get in touch with us!

Northern Romania, mid XIX century

The more “in depth” part of this story begins in the Bihor County in 1841, when the glass factory of Pădurea Neagră (Black Forest) is established. This factory is considered very important and it represents a century and a half of history of glassmaking in Romania.

Today it is only a huge and sad concrete platform surrounded by ruined buildings which make it hard to imagine the times when more than 1,500 people from several neighboring villages were employed here in the production process of a type of crystal glass* appreciated both across the American continent and in old and pretentious Europe.

In 1841, glass articles began to be produced in the Pădurea Neagră. The factory was located on the Bistro Valley, between the mountains covered by centuries-old forests, because there was abundant water, quartz and wood, all necessary for the production of glass. The Bistra water flow covered the needs of production and the population, the quartz, which was in sufficient quantity, was gathered and turned into sand at the mill, and the forests covered for many years the need for fuel to be used to melt the glass mass.

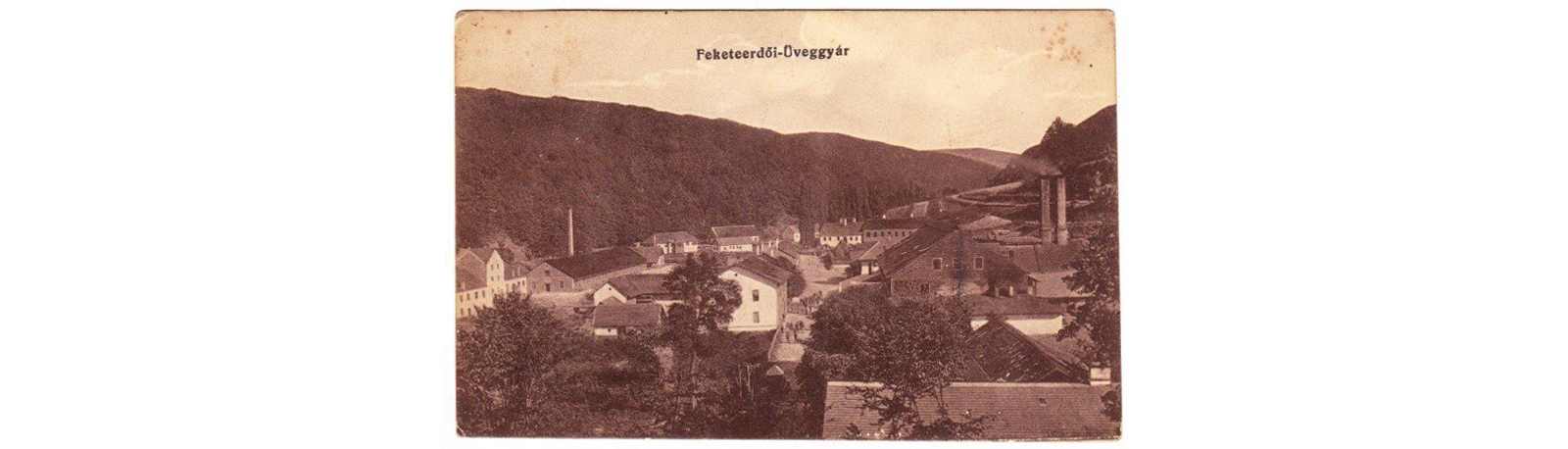

A 1917 postcard with the Hungarian name of the factory.

According to the official website of the city of Alesd, which today belongs to the Black Forest, the first workers were Germans. For this reason they chose Schwartz Wald as a toponym for the place where the factory was located, as the topography and vegetation were similar to those of the German Schwartzwald, which translates in Romanian as Pădurea Neagră, in Hungarian as Feketeerdo and in English as Black Forest.

The Pădurea Neagră Factory became more and more popular and thriving after its connection with Alesd and the railroad through a paved road. The finished products, glassware, were transported in special carts.

In 1909 the factory was taken over by a German company named after one of the most beautiful buildings in Oradea today, the glass shop Deutsch K.I. In that year, Deutsch’s firm entered into a business with the Glass Factory in the Black Forest, forming an anonymous society with a social capital of 700,000 crowns.

Among the characteristic products of the glass factory, marketed in the company’s shop in Oradea, were the large and small preserving jars with “Viktória” caps (pictures not found) which ensured a hermetic closure. In 1917, when the factory was sold, the value of the share capital fell to 245,000 crowns – after the retired shares were redeemed.

The factory continued its activity in the Communist period, under the name Întreprinderea de sticlărie Pădurea Neagră (The Black Forest Glass Company), the crystal glass produced here being appreciated all over the world. Drinking glasses were the main product, but many more were manufactured here in this period: chandeliers, bottles for wine and spirits, ornamental fish and ducks. According to records 90-95% of production was for export to America during this period.

“The crystal glass of Pădurea Neagră was recognized all over the world. When going to trade fairs, they would not even have to make presentations or praise the merchandise, because everyone knew it.

The products were sold all over the world, across Europe, America and Canada. At that time, more than 1,500 employees were working.“ remembers Aleşd Mayor Zeno Dănuţ Ţipţer.

Only a few years after December 1989 came the unsuccessful privatization of the factory, and the story of Pădurea Neagră glass would end abruptly in 1996.

Time cannot be given back, and the glass (or better the crystal glass) of the Black Forest will only remain in the memory of those who have heard its clean clinker. Thrown among the debris, an almost new label for an eight ounce crystal glass to be exported to New Jersey is the living proof of what was here once.

An even older Romanian factory, with a bittersweet story

The Tomeşti Glass Factory was located in Colonia Fabricii, 2 km upstream of Tomeşti, in the non-invasive meadow of the Bega River, between the fully wooded mountains of low altitude. Industrial buildings are placed between the highway and the Bega River before the bridge. The site is tight, but it was taken into account that the level of the groundwater is lower than the ground so that the base of the industrial constructions, respectively the foundation of the regenerating rooms of the furnaces, and the smoke channels, are not exposed to the flood.

The initial reason that determined this site in 1820 was the forest that surrounds the factory. The fact that the location of the factory was determined by the existence of the forests is also mentioned by C. Popescu in the File din istoricul sticlăriei româneşti (“History of the Romanian Glassworks”): <<as all the glass and glass factories built before the First World War, the glass factories in the Black Forest, Poiana Codrului, Tomeşti , Azuga, Avrig were built in the heart of the forests that were to provide them with wood, both for the heating of the furnace and for the production of potash ash, which was then used as the alkaline raw material for glass. “ Another reason was that there were enough raw materials nearby: quartz sand, quartz and limestone. The quartz was mined 4 km upstream on Mount Druja and Catanul (Luncani) and limestone quarries near the locality.

The existence of abundant water (the Bega River) also favored the plant’s location. It should not be forgotten that the surrounding villages: Luncani, Romaneşti, Zolt, Gladna Română, Baloşeşti, offered cheap labor, especially unskilled.

As far as the beginning of the factory is concerned, we do not have the original document at hand. It may not even have been elaborated, given the tendency of the entrepreneur to escape the tax to the Austrian state. However, one thing remains certain: the factory appeared around 1820, although there are some mostly technical works, which date back to 1804.

The owner Anton Pfantzels, formerly a lessee of a glass factory in Hungary, was attracted by the great wealth of the area near the Romanian commune of Tomeşti, the forests, the massive quartz and limestone layers, and the cheap energy of water.

A turn of the century photograph of the factory gates.

Workers of the Tomeşti Factory (1898)

In a short time since the entry into the property of Pantzels, the glass factory was able to become operational in 1826.

In 1846, the factory became the property of Joseph and Leopoldina Losch in Austria, who brought specialists from abroad, skilled workers and set up a school here. Their son, Adolf Losch, who inherited the factory, kept his family’s tradition and continued to produce drawn glass and household glass.

The factory participated in the exhibition of glass products and was awarded for the products exhibited in 1885 in Budapest and in 1891 at the exhibition organized in Timisoara. At that time, the production was 70-80,000 dozen (schock) per year, various items, medical bottles, glasses, services and bottles.

In the second half of the nineteenth century there was no law in Transylvania to protect the interests of workers, and they had to work 16-18 hours a day. Children were also used in the production process. The proof of the use of children and the heavy working conditions we have from a photograph from 1898 (above), which has been preserved so far.

At the nationalization of the industry on June 11, 1948, the Tomeşti Glass Factory operated the two valve furnaces on the place of the two pots. The assortments that were made were expanded in favor of household blown glass articles and lamp articles. By the end of 1948 there were about 200 workers. The first director after nationalization was Ghia Ioan (39 years old).

In 1956 the Tomeşti-Margina industrial railway line was built, thus making possible the connection with CFR Margina railway station which facilitated the transportation of raw materials and finished products.

In 1957, a 6-hour working regime was introduced for glassmakers and mixing workers. This measure, besides the special importance for workers’ health, also had economic efficiency and increased the need for skilled workers (the artisan of these measures was Dragomirescu Dorel, economist in the Directorate). They will be trained through the professional schools in Turda and Medias and through apprenticeship at the workplace for glass and professional schools of M.I.U. from Sighişoara and Târgu Mureş for the mecano- energetic sector.

In 1952 – 1955, the need for specialized technical staff was covered by the incorporation in the factory of several graduates of the technical secondary school that operated at that time.

Between 1975 and 1980, the enterprise developed and modernized. The project was developed by I.P.I.V. Bucharest. The total volume of investments allocated for development was 32,500,000 lei. The construction works were executed by the Timisoara Industrial Construction Trust. A new hall for the finishing workshops was built in the order of the technological flow, ending with a packaging space and finished products warehouse. The old furnace hall was prolonged, a 52 m high chimney was built by the team led by Mitran Ioan from Târgu Jiu. The 39 m high tower was at this point being built and the old annealing hall was connected with the newly built building.

Prosperity lasted until the late 1980s, when the factory began to face the crisis that swept across the country. Many of the products that had made the factory famous were not manufactured anymore, and after 1990 the factory was on the verge of bankruptcy, working to a minimum capacity. The plant was then auctioned for a ridiculous amount. After that first-hand glass craftsmen continued to live in Tomeşti, but there was no more factory for them to work at.

What many documents stress is the high quality of the craftmanship in the Tomeşti Factory: it had first hand glass craftsmen, renowned blowers, skilled painters and engravers, who practiced this profession from father to son. Out of their hands came many wonders, many of them unique, various figures, from different characters and animals to true glass artworks, handcrafted, without a mold.

At least up until the nationalization in 1948 all newly hired glassmakers would attend an apprenticeship before starting their work at Tomeşti under the guidance of old glass masters who taught their craft. The most talented among them had traveled around world-famous factories from far China, where the working technique is like the Middle Ages, to the famous Italian workshops in Murano.

Three glass vases found by All’Origine which are very likely to come from the Tomeşti Factory.

Sources for this article:

http://www.dozadebine.ro/sticla-depadurea-neagra/http://tomesti.ro/2012/03/24/fabricade-sticlarie-tomesti/

https://www.pressalert.ro/2015/02/istoria-dulce-amara-a-celei-mai-vechifabrici-de-sticla-din-romania-cumse-prelucrau-cu-tehnici-medievaleadevarate-opere-de-arta/

https://kitschmuseum.ro/povesteaadevarata-a-pestelui-de-pe-televizor/