Befriending Miklós Onucsán

Befriending Miklós Onucsán

The Romanian Conceptual Artist who Makes Visual One-liners

The career of Miklós Onucsán is a long one. As a Romanian artist he has produced work during the last four decades, under the rule of Ceaușescu (1965 – 1989), after his downfall during the post-revolution period and during Romania’s membership in the EU, from 2007 until present days.

Onucsán is often referred to as a “post-conceptual” artist, but we prefer the definition of a conceptual artist who has developed a visual language that happens to be incredibly aesthetic. His works are usually subtle and thought provoking, they have a goal to raise societal, behavioural, political, and even existential questions, but usually in an indirect and open way. He has said in interviews that his art does not offer answers, only questions, perhaps “takes” on our reality, we may add. Some of his works are on the great scale of spatial installations. Labor intensive for the artist and immersive for the viewer. Others are but casual snapshots with a witty title that fills an otherwise dull image with humour and meanings. The latter make you smile in a split second and keep you thinking for a while. Dare I say these are “visual one-liners” highlighting paradoxes and tragicomic aspects of the reality that surrounds us. Things that would be completely missed without the artist’s intervention: Miklós Onucsán is the Mitch Hedberg of the visual arts world!

Miklós Onucsán, The Column with an End, 2011, digital photo, dimensions variable.

Miklós Onucsán, Terrestrial Rainbow, 2005, digital photo, 32 x 47 cm.

Miklós Onucsán,The Restoration of the White Camouflage, 2019, site-specific installation (scaffolds, digital print pn backlit banner), The Romanian Pavilion, Giardini della Biennale, Venice.

“Davide changed my prejudices about the arrogant Westerner, who looks at you with superiority.”

Onucsán is our seventh Guest Curator. Over the past years we have had the honor to work with architects, designers, artists, photographers and art directors. Each Guest Curator was invited to use All’Origine as a source of inspiration and physical materials to develop one or more collaboration projects.

But the case with Miklós Onucsán is a bit different. We have indeed already worked together many times over the years: we provided logistic support for his Venice Biennale installation “Restoration of the White Camouflage” (2019) sourcing scaffolding and other materials; we also supplied some of the rubber rollers he used for “Proletarian Frescoes (an affective archive)” (2024) which will be presented towards the end of this article as our collaboration project. But what makes this interview so unique are the deep common roots we share. So deep that one could think we have been secretly consulting with him since he first met our founder Davide around 25 years ago.

So we will not follow the usual path with a clear distinction between the overview on the Guest Curator’s career-defining projects and the collaboration projects with All’Origine. We will instead try to draw a parallel between the thoughts and sensations evoked by Onucsán’s work and the ones that inspire All’Origine’s daily activities. Our thesis: if there is something that makes you feel attracted towards our European mid-century Originals, you will be drawn towards Onucsán’s art as well!

Davide and Miklósin 2011 near Capri Island.

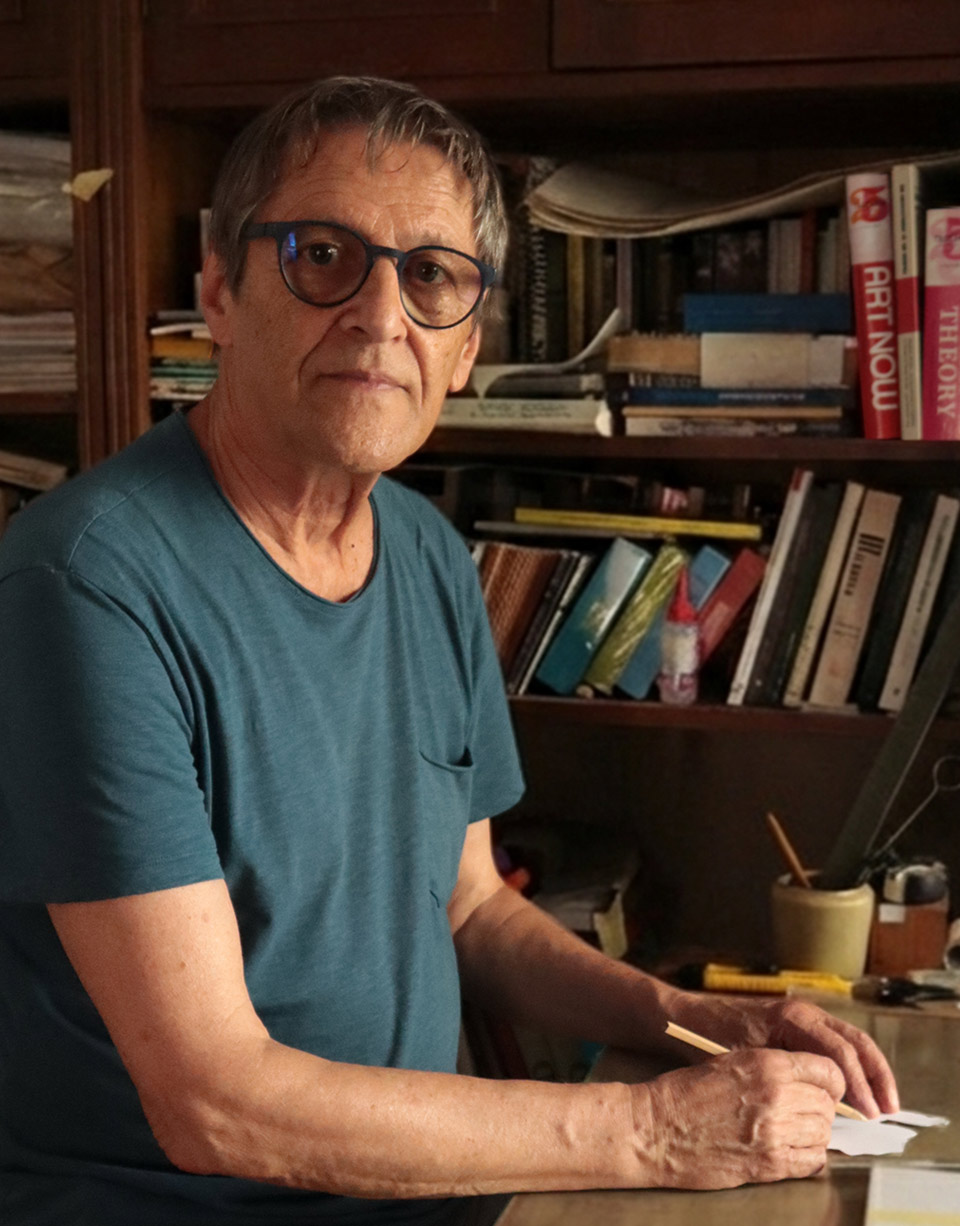

Born in Gherla in 1952, Miklós Onucsán is considered one of Romania’s most prominent living artists. He is formally trained in ceramics but (just like our previous Guest Curator Simone Luschi) he chose to abandon this medium right after completing his studies. To this day he lives and works within the borders of his native country (in the city of Oradea since 1979) while his works are displayed in galleries and museums all across the globe.

Our founder Davide, born in Imola in 1975, also has deep ties with Romania. He is fluent in the language, has spent 10 consecutive years of his life living in Oradea (between 1995 and 2005) where he met his wife Gabriela, and continues to travel to Romania every few months for business.

Corina Jucan, with All’Origine since 2012 and Art Director since 2015, has been stably living in Italy since 2006. She is a Facultatea de Arte alumna from the University of Oradea, an institution where Onucsán also used to teach for a few years in the early 2000s.

Even if we’ve never branded All’Origine as a company with Oradean roots this is most definitely the reality.

This Romanian upbringing, in those specific years, the material culture and the shared collective memory are surely among the reasons for this incredible closeness that we feel. Through this article we wish to explore, as usual lightly and not claiming to be exhaustive in any way, this artist’s vision and to draw a parallel between his approach to conceptual art and our thoughts about objects of the past. Onucsán is about to be asked 10 questions, each revolving around a specific theme-word that seems meaningful in his practice. We will present one of his works to embody each of the ten concepts. Alongside each work we will also present an All’Origine object, selected specifically for this list in a joint effort with Miklós Onucsán himself.

1_Dialog

G. Dialog is the title of your first Exhibit with the Atelier 35 collective back in 1981. And a characteristic of your work is to be dialogic: your whole production sparks questions and opens debates. But before I ask you about your work could you tell us how you met Davide? What was happening in Romania at the time?

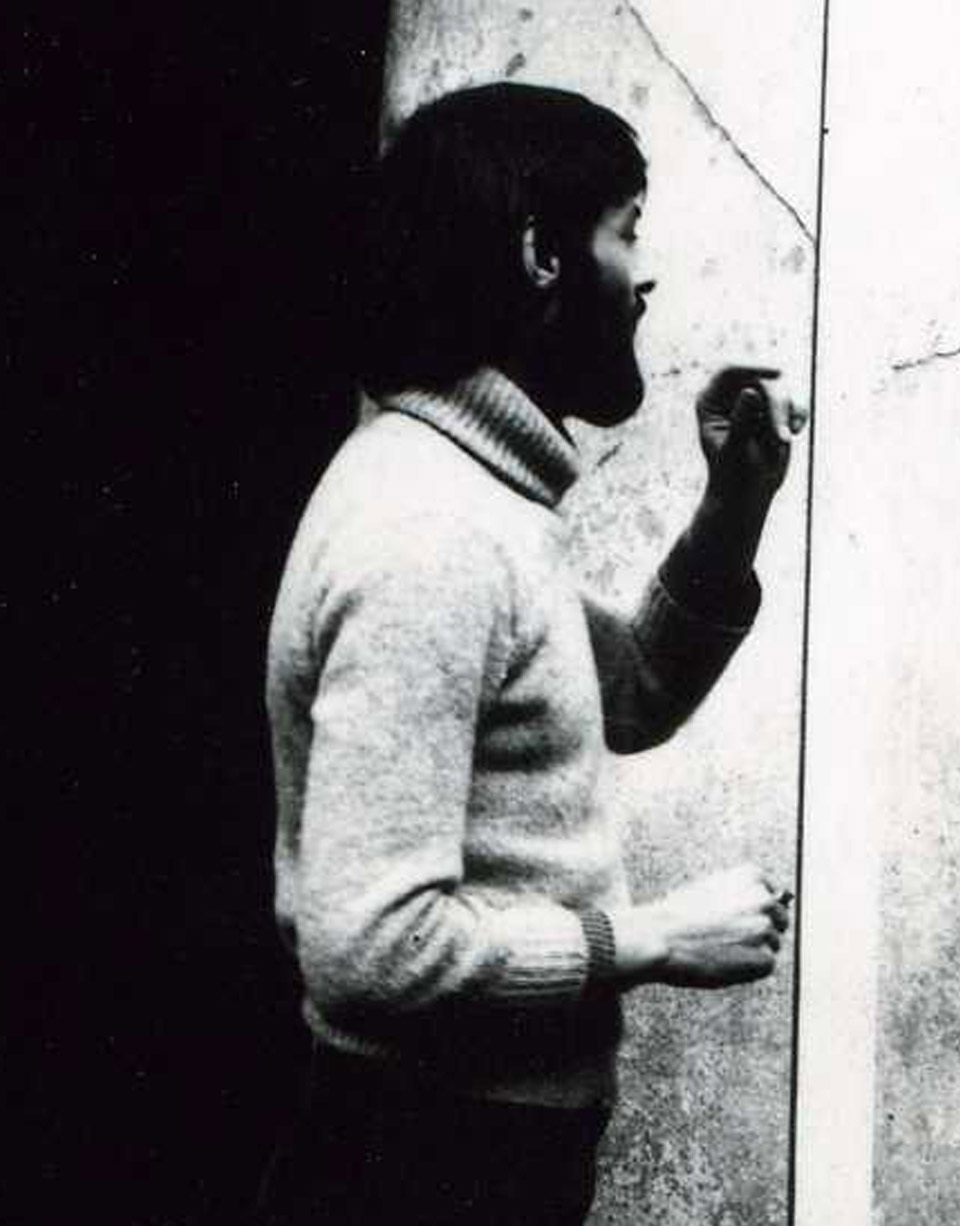

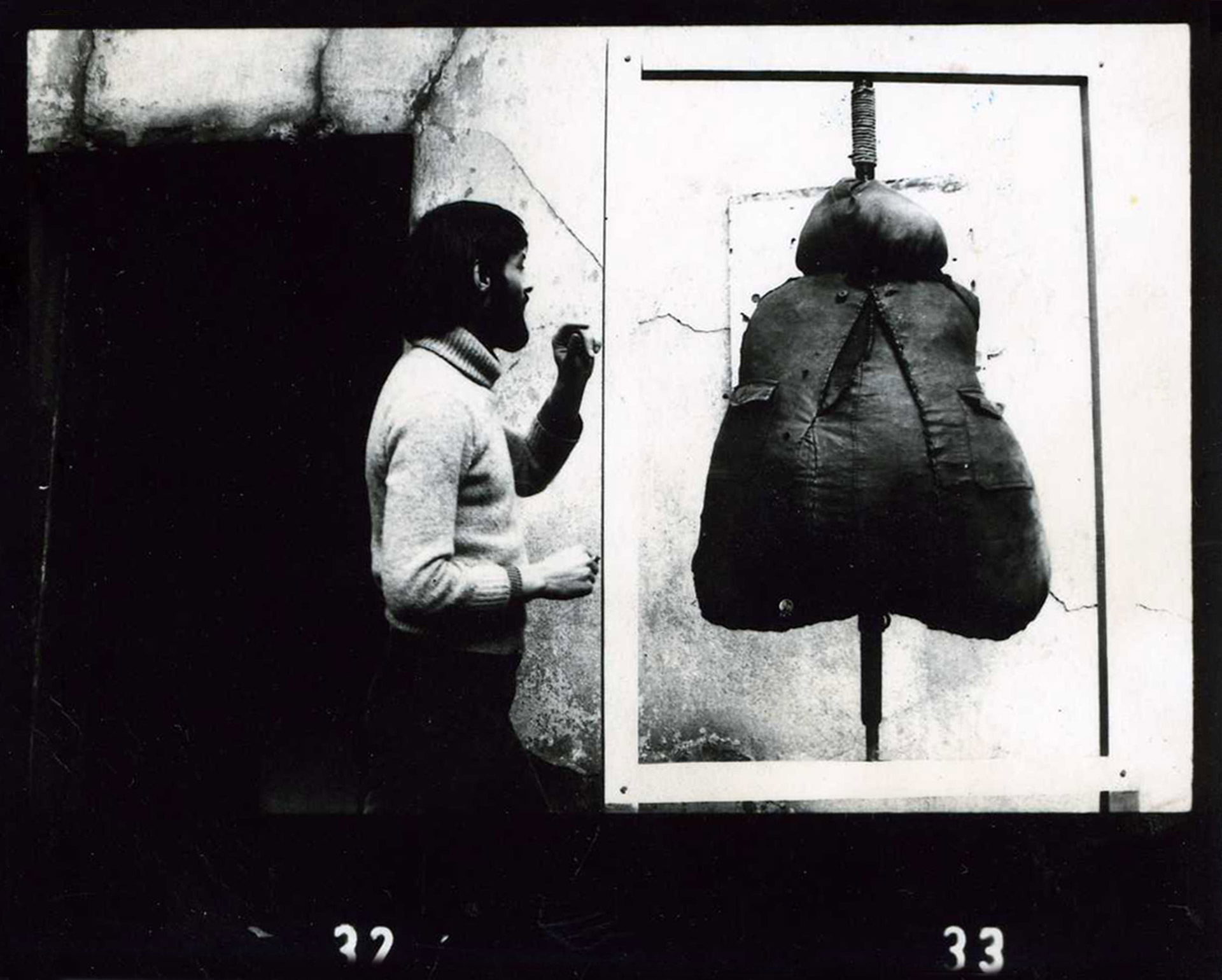

Saint Sebastian, 1981, assemblage (stuffed military coat, tar, wooden frame, photos), 210 x 70 cm.

M.O. As far as I recall, I met Davide in the early 2000s. We met in Oradea, through mutual acquaintances. Davide had been in Romania for a few years, when I met him, he already spoke Romanian, otherwise we probably wouldn’t have become friends as quickly. He was an exotic character for these places, an Italian who came to a place where people wanted to leave from. Romania was, at that time, a closed country, at least for us. A country we could hardly leave, travel from – assuming we had the means to – because we needed visas to go anywhere, and visas were hard to obtain. Although the millennium had changed, things here still looked like an extension of the terrible 90s, a very difficult period, in which the entire country’s economy was in free fall, industry had been completely destroyed, unemployment had reached record levels, and the country looked accordingly. I found Davide’s occupation, hunting for antiques and vintage objects, very interesting, and I was surprised that he could make a business out of it. Very quickly, in the wide circle of acquaintances and friends in Oradea, Davide became a kind of hub, his house was always open and we gathered there very often, more organized or spontaneously.

Davide changed my prejudices about the arrogant Westerner, who looks at you with superiority, and I think not only for me, but also for his collaborators here, who were part of all social classes and ethnicities. I remember with great pleasure that Davide’s Roma collaborators were also invited to his wedding with Gabriela, and they honored the invitation – a fair treatment that is quite rare in our society.

G. Could you tell us something about that first exhibit titled “Dialog”?

M.O. Dear Gianluca, I believe you’re investing too much in this exhibition, it wasn’t all it might seem now. Dialog was a group exhibition, I just joined it, it wasn’t my idea, it wasn’t me who gave it its title, so I don’t have some special merits for it. The exhibition was asking the participants to engage in a dialogue with a famous work or motif of the canonical history of art. I chose the motif of Saint Sebastian, which I reinterpreted through an object I once spotted on a field used for military training – a stuffed human bust, made of a military cloak, on which soldiers practiced bayonet shooting.It was a generic image of the human-as-target.

G. Could you expand on the “ways in which” and “reasons why” your work is dialogic?

M.O. I believe any work of art is dialogical: first of all, it attests to a dialogue between the artist and the idea, or a dialogue between the artist and the material. But, given the exhibitionist character of art, by showing others what you do, you’re implicitly engaging in a dialogue. The work of art is the means through which the artist discusses with her / his peers, irrespective of who is the one who’s making that work, or of how the work looks like. My works are just modest reaffirmings of this evidence.

From All’Origine’s selection: detail of a composition by Corina. Objects from different decades and of different European origins are brought together establishing a visual interaction.

2_Decay

G. We seem to share a fascination for things that are not in their prime anymore. Most old artifacts have had a brief period in which they looked “fresh out of the box” and then a much longer one in which they present increasing signs of the passage of time. There is a point when they are too far gone, which we try to offset as much as possible through conservation here at All’Origine. Yet we never wish to erase the signs left by time. We always preserve patina and scars. Signs of decay are visually pleasing to us and are “proof that something happened among people” (to paraphrase Claude Lévi-Strauss). Why is decay important in your art?

Miklós Onucsán, Beware! The Daub is Falling, 2013, object (engraved marble plaque), urban intervention, 52 x 40 x 3 cm.

M.O. I cannot say if it’s decay in itself holding a certain place in what I do, or if it’s rather the processes of transformation that take place in time and leave traces. Decay is one of such processes, but not the only one. There is a very ferocious and alive boundary between decay and transformation, they go hand-in-hand, and form a vicinity to one another where it’s very hard to establish clear limits. The decay carries with it an imminent tragic note of dissolution (whether we’re talking about objects or the spirit), whereas transformation is more multifaceted. For this reason, the idea of transformation seems much more accessible to me, and I explore it in various ways in several works.

In “Beware, daub is falling!” I was referring to a certain dialogue between the political/administrative power and the citizen. It is not a celebration of the decay, but an irony of the so-called care with which it became customary, in Romania, to signal the facades of buildings from which pieces of debris fall onto the street, over people’s heads, by discreetly displaying notices, usually printed on A4 sheets, reading “Beware, daub is falling!”. If the citizen has been warned, there is no longer any responsibility in the event of an accident. I inaugurated one such marble plaque in two cities in Romania and gave an inauguration speech, as is customary on such occasions: “We have gathered here this afternoon for a brief festive moment, to inaugurate a commemorative plaque that will mark this place, with one of the signs of the present, for memory and for future generations. This plaque that we are unveiling now is meant to remind us of the permanence of movement, to celebrate the continuous and irrevocable transformation of the traces of the past, which we have all been witnessing for a long time now. This process is a one-way street, from which there is no turning back, and the commemorative plaque we are inaugurating now is here to mark precisely this state of waiting that characterizes our present. It will remain here as a lasting reminder of an implacable ephemerality. Thank you.”

M.O. When degradation is tempered by conservation, as you do at All’Origine, what results is cultural heritage. But when degradation is ignored for too long, what results is an erasure of cultural memory, and that’s more likely what is happening here, in Romania.

From All’Origine’s selection: heavily deteriorated mastershapes used to cast molds for ceramic hands and forearms, later to be used themselves as molds in the manufacturing process of rubber gloves (Bulgaria, circa 1970s).

3_Traces

G. Finding traces of other human beings is always thrilling. When we find the sign of a deliberate action on an object, especially if we can give it a meaning, we get excited as if we had found a message in a bottle washed up on the shoreline. As in this parallel, it’s not really the message itself that matters, it is riveting to get a little glimpse into someone else’s life. Someone we know so little about that they become an archetype for mankind in general. Much of your work also involves leaving traces on objects or documenting traces left in a predetermined process. Where does your interest for traces stem from? How has this practice evolved over the years, from your early works until now?

Miklós Onucsán, The grateful posterity, 1998, photo-documentation of the action Co-memoration (salt plaque, sheep heard), dimensions variable.

M.O. The occupation I have does nothing else, basically, than it imprints / leaves traces. Whether they’re provoked, invented, or found traces. Leaving traces is inevitable in visual arts. I don’t know if we can talk about an evolution per se in my work or about an accumulation of experiences that became more and more diverse. I’ve always worked outside the so-called canonical media of visual arts, which offered me a different freedom of thought, association, and materialisation. Sometimes, I’ve found ready-made images which only needed a title – like the 6-meter piece of foil stained with large and expressive rust spots, which I found thrown away somewhere and which I exhibited under the name “The History of Rust from Its Origins until Today”, making an ironic reference (again) to the supposedly exhaustive histories that are rewritten with each major change of political regimes. Other times, I had ideas that required a specific type of materialization – there are many examples, but I would mention “The Grateful Posterity”, a happening that had a flock of sheep as its performers. I was in a creative residence at Salina Turda, a salt mine dug by former convicts who often died there due to hard labour, and which is now used as a treatment facility. I made a commemorative plaque (once again), out of salt, with the inscription “The Grateful Posterity”, and I took it to the middle of a flock, so that the sheep would carry out the enunciation of the plaque, licking it until its disappearance. Of course, the sheep were a metaphor for us humans, who are only able to appreciate events or individuals of the past that did not receive any attention at the time.

“Shortcut” was an idea based on the observation that, in the spaces we inhabit, we’re circulating more intensely in certain directions, and on specific routes. As a result, we “beat” some paths, which can even become visible if the parquet or carpet is not changed too often, over several generations. The Persian carpet was a status symbol, some people kept the carpet on the wall or covered it with a protective foil, so that it would not wear out. For this reason, the Persian carpet offered itself as a suggestive support to visualize such a path of wear.

Miklós Onucsán, Shortcut, 2006, object, 349 x 224 cm.

From All’Origine’s selection: an old wooden pitchfork with repair work done by the original owner. A tin lid off a branded can (presumably from a product they had previously consumed) is repurposed as a patch.

Miklós Onucsán, The History of Rust from its Origins until Today, 1986, found object, 200 x 600 cm.

4_Time

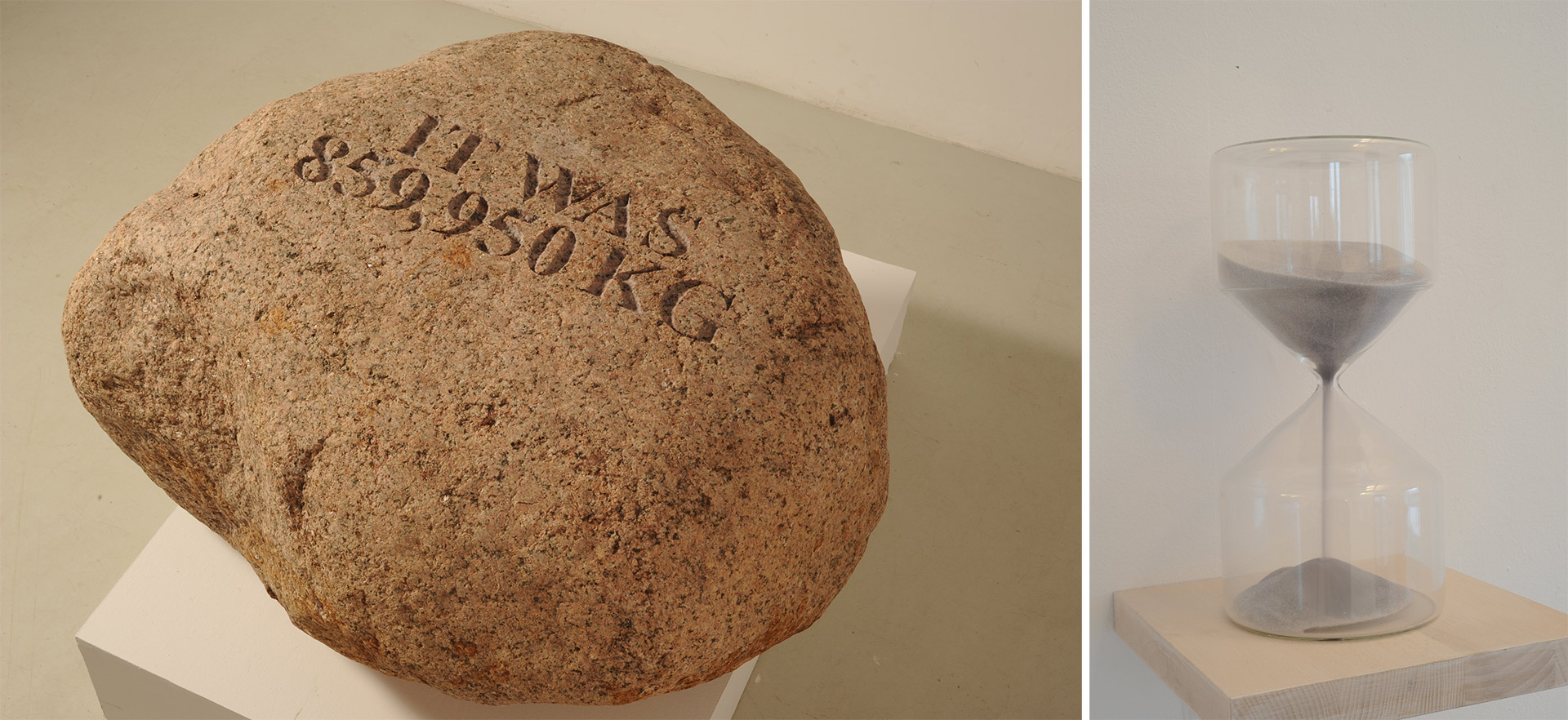

G. This word can be linked to very many of your works. A particularly obvious example I would bring is “Unfinished measurements II” where you weigh a stone and engrave the measurement on its surface in a process that renders the measurement inaccurate (as material has to be removed to achieve the engraving). The pulverized stone obtained from the engravings is then put inside a custom built hourglass. Through our many biases of “vintage lovers” there are two messages we take home from this work: firstly, that trying to freeze something in time is a futile effort. Does time work against you or with you?

M.O. I’ve always liked to say (and believe, to a large extent) that if you forget about time, time forgets about you. This reciprocity is an artificial one, of course. But I liked the idea that by forgetting about time, time evades the memory, it doesn’t exist there anymore. I liked this saying because it contrasts with the worries of most people, who increasingly complain that they don’t have or no longer have time for various things.In relation to such concerns, I find my reply to be valid. At a larger scale, all of our existence is marked by time, and my saying refers to the so-called attempt to escape from the aegis of time.The goal is not, by any means, eternity, but that freedom that places time on a secondary level. By constantly keeping track of time, you’re guaranteed to never have enough time. After all this, what do you think, is time working for me or against me?

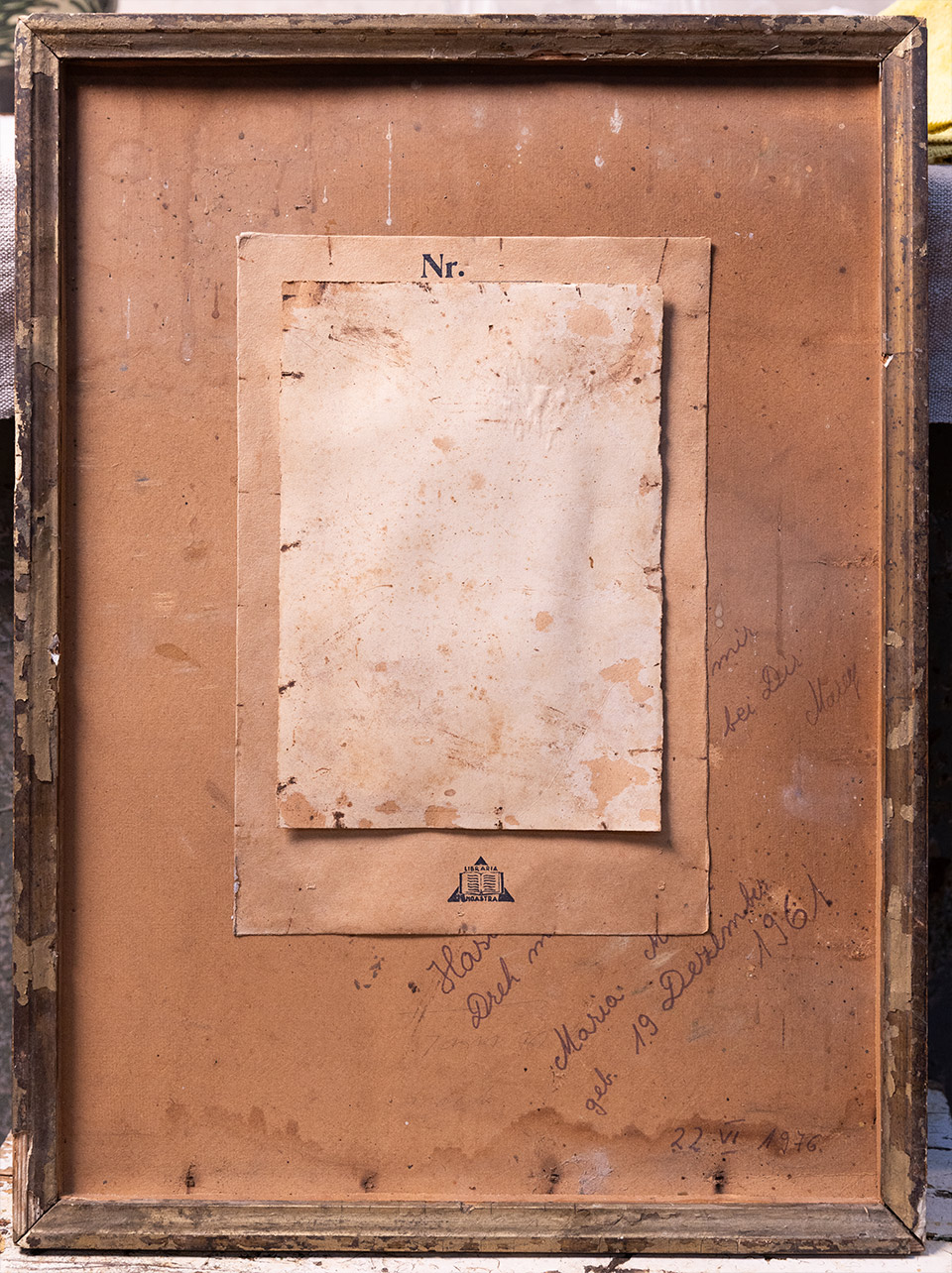

From All’Origine’s selection: a composition made overlaying old backdrops, previously unframed from large pictures. Dates have been scribbled on one of them many years apart.

5_Inaccuracy

G. The other consideration that sparks from “Unfinished measurements II” is that there will always be something we can’t fully grasp: 100% accuracy is never possible to achieve. At times it literally seems to move away as you get closer to it! In our practice this can relate to our identification efforts, to the little tidbits of knowledge we are able to gather around an object, its manufacturer and designer: more information we gather, more we feel like perfect accuracy moves a little step away from us. Are you bothered by our impossibility –as humans – to ever be fully accurate?

Miklós Onucsán, Unfinished Measurements II (towards an archive), 2014, installation (engraved stone, hourglass, stone-sand), dimensions variable.

M.O. No, quite the contrary! I think that the impossibility of ever being completely accurate is what defines us as human beingsand as simply living beings. Diversity, in all the natural reigns, is given by as many imprecisions that manifest themselves within precise limits and in perfect harmony. One can precisely affirm about all that is alive that it is imprecise. And the products of our cultures keep this imprint of inaccuracy in their turn.

From All’Origine’s selection: a vase attributed with absolute certainty to German potter Max Laeuger (circa 1920s).

6_Ephemerality

G. There is another artwork from this series I would like to touch on: “Unfinished measurements III”. You use stone a lot, I think playing on the desire of mankind to make something that lasts forever, but making a sort of joke about it. You actually use stone against the principle of durability! With the 8 consecutive text carvings on a slate that each time is made thinner to erase the previous one, you seem to accelerate a natural process to highlight the fact that what looks immutable is actually ever changing (even if very slightly). In this performing piece the slate ends up vanishing completely. Can you expand on your interest for the ephemeral?

Miklós Onucsán, Unfinished Measurements III, 2014, process and installation (marble plaque, 52 x 40 x 0,2 cm; documentation photos, dimensions variable).

M.O. I had no intention of being humorous with this work, but rather very critical. The commemorative marble or stone plaque is the simplest form of the historical monument to be exhibited in the public space (with the more complex forms being the busts, the equestrian statue, the statuary groups, etc.). But not all the political regimes are celebrating the same historical event or characters. When the political regimes changes, the content of the commemorative plaques or the characters of the public monuments also change, just as the name of the streets change. At least in our part of the world, such practices have occurred at fairly short intervals several times over the last eight decades.In my work, I did not want to mention a specific event or character, but to invoke this practice of replacing public memory with another version accepted as official or the “true” one. And I asked myself, what would happen if this entire sequence of changes were to be applied to the same marble slab – eventually, the slab would be erased to the point of disappearance.In a way, my thinned marble slab is a metaphor for the collective memory of recent local history, so many times erased and replaced that it no longer has the capacity to record new versions, or to fully remember any of the older ones. The ephemeral appears in this work where, in reality, there should have been a longer form of continuity. As Milan Kundera, another Easterner, wrote: “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting”.

From All’Origine’s selection: antique frames and bits of stucco fallen from similar artifacts. The latter are preserved and repurposed by Art Director Corina Jucan for custom projects.

7_Pattern

G. The word could be pattern or repetition. There are behavioural patterns that you document through your artworks and there are visual patterns that derive from your process. Instead of going for the “visually obvious” patterns I would like you to tell us more about your projects that investigate behavioural patterns. One that strikes me in particular is “Portret de grupneintentionat” (2012). Standing at a crosswalk with a hidden camera you shot pictures of the people gathering on the opposite side waiting for the light to turn green. You said this is the opposite of any normal group photo (like photos taken at graduations, weddings or in the military) where subjects share a recent past leading up to the event of the shot and then disperse into the world: in this case everyone is coming from a different path/past and what they will share is the brief walk across the road that awaits them in the imminent future. This work is incredibly evocative of our practice here at All’Origine, where we put collections together for a brief period of time, pairing objects from all corners of Europe which after a brief period together will be dispersed again towards different clients. But there is one key difference: our objects have no free will, your subjects for this project do! Yet you witnessed an unexpected phenomenon: almost everyone instinctively lined up and made a perfect pose for your photo without any input from you. Are people this predictable? Do you find patterns reassuring or do they scare you?

Miklós Onucsán, Unintended Group Portrait, 2012, photographs, open series, dimensions variable.

M.O. For each unintended group portrait I photographed existed another matching group portrait, also unintended, of which I was a part too, standing on the other side of the crossing, and which did not remain in any image. I think people are very predictable, they feel the need to know they fit into one pattern or another. It depends on the pattern, but some can be very unsettling.

From All’Origine’s selection: a group of mid-century drinking glasses sourced between Romania, Germany, Hungary and Poland.

8_Mundaneness

G. Another piece I often find myself thinking about is “Tipar pentru a sfera” (2012). Which could have also been a good pick for a question on visual patterns. It is quite remarkable how you are able to make us stare at something so mundane and completely unaltered as a series of orange peels. I mean, not that an orange isn’t something amazing per se. Bruno Munari famously brought it as an example of the perfect self packaged and pre-portioned snack designed by nature. What I mean is mundane things can be amazing but they are generally overlooked.

From a business perspective I would say this is the very intuition Davide had when many years ago he decided to shift from proper antiques to more humble everyday objects.

I would like to know if there is a reason for your interest in the “uninteresting” and if you feel you have a role in guiding people’s perception of the ordinary. Or perhaps to guide perception through the ordinary…

Miklós Onucsán, Pattern for a Sphere, 2012, digital print and / or objects. Objects’ dimensions: 36 x 36 x 3,5 cm (framed). Photo: Trevor Good.

M.O. I don’t want to guide people in any way, it would seem an arrogance of me to have such a goal. I’m the one who’s being guided by the different things I encounter and which inspire me ideas. If these end up meaning something to others as well, then that’s all the better, but I never set out with the intention of guiding people. Regarding the ordinary, the question is what does “ordinary”, “uninteresting” mean? If a small thing proves suited to materialize an idea, then is that thing uninteresting anymore? In other words, unconventional means can be more than worthy tools to materialize some ideas. In “Pattern for a Sphere” I actually conceived some instructions based on which anyone can complete the work – and I made a few examples myself. Basically, I found a formula that allows you to create infinite variations of spherical patterns from citrus peels. I found it fascinating! They will never unpeel in the same shape, it’s impossible. It is a work in which the imprecision, which we talked about earlier, and the diversity to which it inevitably leads, are brought to fruition.

From All’Origine’s selection: a collection of old trowels initiated by Davide.

9_Relativity

G. You famously said “white becomes darker with wear, black becomes lighter” so the color white could be seen as a very worn out black and black as a very worn out white. Through works like “Este Diferitpentru ca este identic, este identic pentruca estediferit II” (2012)- also a good example for the use of mundane objects- you find diversity in what looks the same or perhaps you celebrate sameness in what looks diverse. This is once again something that is part of our daily routine when we put together collections of very similar (yet unique) objects. There are predetermined categories in our mind, let’s say “brass candle stick” just to pick an example from All’Origine’s catalog: if a person were asked to think about them, all candle sticks would be envisioned as the same object, identical in the projection a human brain can produce unless specifically interested in the subject. But if one were to actually start a collection, they would realize there are many typologies and infinite variations within each one. Yet depending on the context we could agree with both statements: candle sticks are all the same. Candle sticks are all different. I would really have a hard time saying either statement is universally true.

How do you feel about absolute truths? Does your art look at the polarization that is happening in the world around just about all the topics that are part of the public debate? What are your unshakable beliefs?

Miklós Onucsán, It’s different because it’s the same, it’s the same because it’s different II, 2008, object, paper, 50 x 50 x 10 cm.

M.O. I do not believe in absolute truths. Attempts to implement absolute truths throughout human history have created and continue to create the most terrible anomalies. I believe that art in general – not just what I do – remains one of the essential bastions of sabotaging and questioning all claims to absolutization. These are my unshakable beliefs.

From All’Origine’s selection: details of the bases of three candle holders.

10_Memory

G. Someday I will surely be able to interview someone without talking about death. Today is not that day. You’ve highlighted many of the dichotomies that underline your whole body of work: ephemeral/eternal, specific/universal, temporary/irreversible et cetera. So rather than speaking about the condition of being dead (which is indeed a rather unfortunate one) I would like to talk about memory, which is the gift of the dead to the living. So not a proper dichotomy, but a sort of exchange hub between two opposite conditions.

When Napoleon issued the Saint-Cloud decree, imposing to bury the dead outside the perimeter of cities in anonymous graves, he sparked a lot of outrage. Italian poet Ugo Foscolo wrote a whole Carmen (I Sepolcri) to educate him on the importance of preserving the memory of those who have passed. And while all conservation efforts here at All’Origine serve a documental purpose, there are a few objects the preservation of which has a deeper, “monumental” value.

In “Here Rests the Grass” (2008) you strike a parallel between human death and the death of grass. Tombs marked by headstones for people and a haystack representing itself in a monumental form after having been cut down. I believe you’ve already made a statement on the impossibility to preserve memory for the generations to come through “Pentrupersistentamemoriei”, the commemorative plaque made of ice that melts in the sun, but do you think memory –even if temporary- is important from a civil and moral perspective? What is the legacy that you hope to leave through your work?

Miklós Onucsán, Here Rests the Grass, 2002-2008, digital print, dimensions variable.

M.O. Memory is very important, especially if it is maintained without falsification or distortion, and this is where I think we have the biggest problems. Memory, like truth, cannot be absolute. As for the legacy I hope to leave, perhaps it is a simple and natural question, but for me it is neither. Maybe because I still feel too young to think about it.

From All’Origine’s selection: bust of Bulgaria’s Tsar Boris III. Manufactured in the late 1910’s or early 1920’s, beheaded in 1943 after the Tsar’s sudden death.

G. And lastly, as promised in the beginning: please tell us about the latest project we’ve helped you with by sourcing some materials. What is “Proletarian fresco” about?

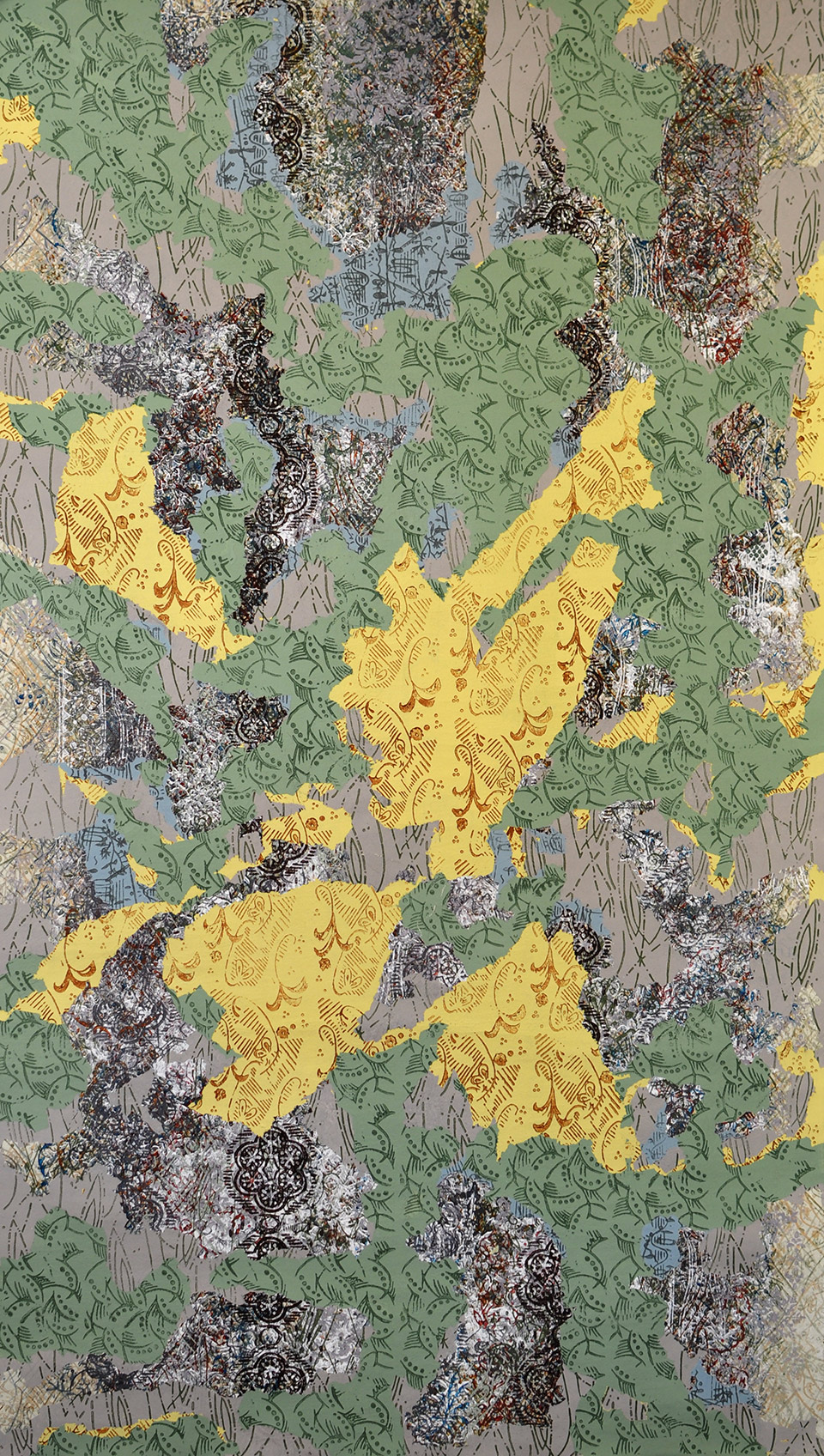

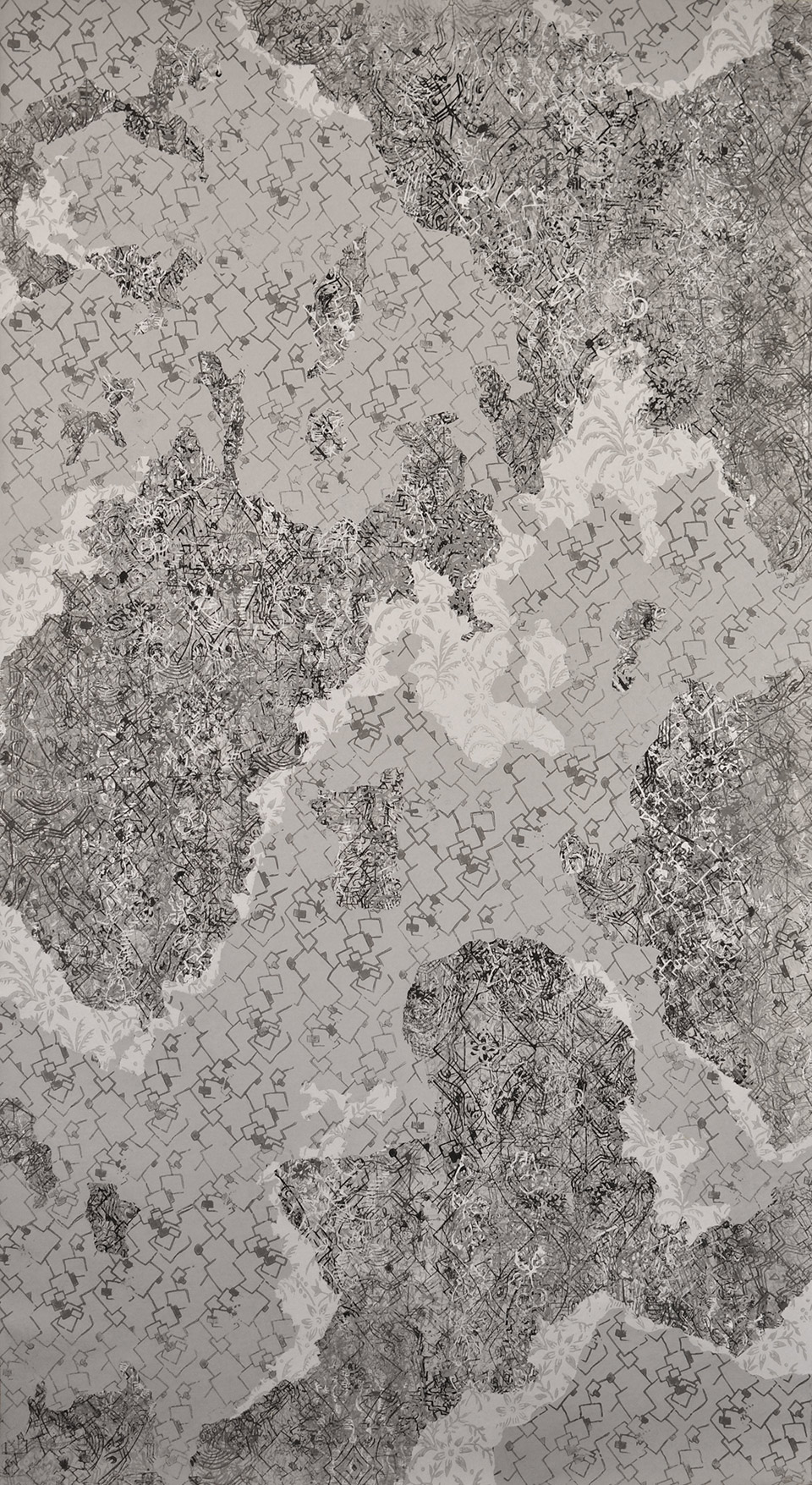

M.O.When I was little and the house was being painted, I would watch in awe as the painter, holding a tool in his hand, decorated the plain wall with a printed, geometric or vegetal pattern with a movement that started from top to bottom.Over time, this way of decorating rooms began to seem ugly to me, but it was very widespread, not only in private homes, but also in the hallways and staircases of apartment buildings or in institutions.A third stage was when I saw these painted walls again during some house demolitions, and then I felt a nostalgia for these images that were very familiar to me.That’s when the title of the project was formulated: these were the frescoes of proletarian houses! It was a slightly ironic and self-ironical title.And when I saw the rubber rollers and that incredible diversity in your collection, I thought of creating a palimpsest, in a series of canvases painted with tempera, that would form an affective archive of images that still have a very strong resonance in the visual memory of this region.

Miklós Onucsán, Proletarian Fresco (an affective archive), 2024, tempera on canvas, 199,8 x 105,5 cm.

Miklós Onucsán, Proletarian Fresco (an affective archive), 2024, tempera on canvas, 191,5 x 105,8 cm.

Miklós Onucsán, Proletarian Fresco (an affective archive), 2024, tempera on canvas, 194,3 x 106 cm.